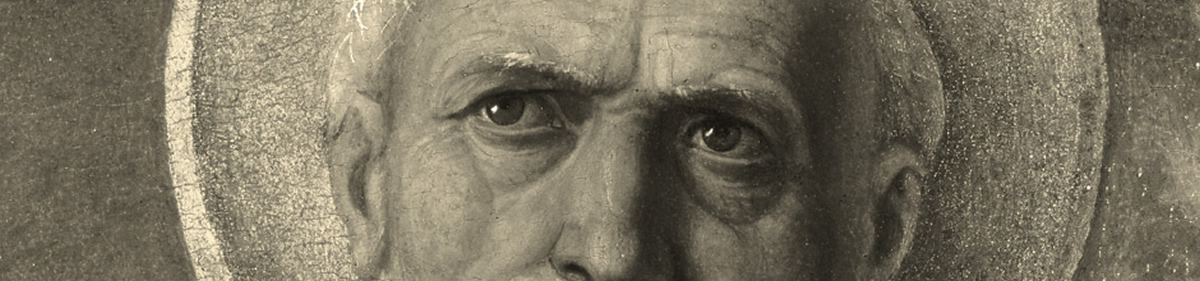

The painting 'St Mary Magdalene, St Blaise, the Archangel Raphael with Tobias and the Donator' was painted by Tiziano Vecellio around 1550. After several repairs and an attack on the painting during 19th and 20th century, this valuable work was properly conserved in the Zagreb workshop of the Croatian Conservation Institute between 2001 and 2006. Today it is exhibited again in the Dominican monastery in Dubrovnik.

The oldest historical reference linking the painting in the Church of St Dominic in Dubrovnik with the greatest Venetian painter of the 16th century is recorded in the first printed history of Dubrovnik of 1595. The Dominican Serafino Razzi mentioned “a work of the celebrated Titian” on the altar of St Mary Magdalene, describing the lavishly appointed interior of the then church of the preaching order. Alongside the sainted penitent, to whose cult the Dominicans were particularly devoted, also shown on the altarpiece are St Blaise, patron saint of the town and Archangel Raphael with Tobias by the side of the kneeling donator. According to tradition, which has not yet been borne out by any documentation, the altar belonged to the patrician Pucić family. This commission puts them in the trend towards ambitious artistic commissions manifested by the Dubrovnik patriciate in the 16th century.

The works of Tiziano Vecellio (Pieve di Cadore 1488/90-Venice 1576) have always excited a lively interest, both among his contemporaries and in their successors, giving rise to imaginative local traditions and casting a haze over the sometimes meagre historical facts. The ample reception and fortuna critica of the Dubrovnik Magdalene was no exception from this point of view and shares the fates of many works ascribed to Titian that were neither signed nor dated, the painter’s patrons not being recorded in documents. In the many opinions and value judgements of this Dubrovnik painting, there have been different evaluations as to its artistic characteristics and what the share of the master’s hand was. Since the fundamental monograph on Titian by G. B. Cavalcaselle and J. A. Crow of 1877, authors who had the chance to see the painting in Venice, the Dubrovnik Magdalene has been considered a part of the master’s oeuvre. More recent criticism puts the date of the picture at about 1550, indicating a smaller or larger share taken by the workshop, with the help of which Titian produced many commissions in the period.

The recently concluded restoration works have considerably enhanced the legibility of the painter’s handwriting and the chromatic relations, allowing for a more credible comprehension of the visual and stylistic features. Backed up with scientific research and an insight into the painting technique, they have enabled a more detailed comparison to be made with the master’s manner of work, particularly with solidly dated works of the end of the fifth and the beginning of the sixth decade of the 16th century. The characteristic formal treatment with colour, particularly in the details, and the suggestive colouring of the plastically emphasised figures on the altarpiece of the Dominican Church in Dubrovnik have confirmed the thinking of leading experts in the oeuvre of Titian such as Rodolfo Pallucchini and Grgo Gamulin, who recognised “the hand of the master” in the creation of this Dubrovnik painting.

Conservation and restoration operations on the painting

The increased interest in Titian’s Mary Magdalene spurred by programmes of big exhibitions during the last could of decades brought into focus the need for restoration works. After a period of investigation and numerous consultations, the conservation and restoration operations were started in 2001 in the Croatian Conservation Institute in Zagreb, almost a century and a half after the previous complete restoration carried out in Venice, and fifty years after the articles of Grgo Gamulin and Rodolfo Palluchhini in which this work of Titian was described as too neglected, illegible and encumbered with overpaintings of the nineteenth century.

Photo Album

Although numerous items of damage to the paint layer were identified by X-ray and IR imaging, it was only during the operations that their true diversity was revealed: from large zones of flaked-off paint alongside the edges of the format, horizontal bands of missing and crumpled paint, the consequences of the rolling of the canvas, to thousands of slight damages to the paint layer which because of the weakening of the binder had flaked away from the ground. The state of preservation and the as-found condition of the altarpiece were to a great extent the consequence of events that marked its history during the 19th century. According to oral history, the Dominicans took the painting down from the altar and hid it in order to prevent it from being looted in the final days of the French siege of Dubrovnik. In 1859 Count Pucić sent the heavily damaged painting for restoration to Paulo Fabris, the chief conservator of the Doge’s Palace in Venice. Following the doctrine of total simulation of style, Paolo Fabris had made his name for his skilled reconstructions of missing form and in particular for his convincing imitation of the facial expressions found in Titian. But his retouches unnecessarily covered parts of the well preserved original. Adroitly reconstructing the cloak and the arm of St Blaise in the sleeve, the locks of Mary Magdalene and Tobias and in particularly the folds of the drapery in the lower part of the painting, Fabris paid scant attention to many remainders of the original paint. Sometimes he painted over important parts of the form like the bishop’s cloak alongside the left hand edge of the painting.

The programme of the restoration works of the Croatian Conservation Institute had three major objectives: to achieve better adhesion and consolidation of the weakened structure of the paint layers, to remove dirt and yellow varnish in conjunction with investigating the later interventions that affect the legibility of the visual form and the chromatic values, and were to a large extent to be blamed for the lack of certainty in the judgements of art history, and, finally, by choice of the appropriate method and the execution of retouches, to enable the extant parts of the original formal treatment to prevail in the visual experience of the whole.

Although this Titian painting was among the rare works of art in Croatia to be covered with lively interest on the part of the professional public during all phases of the operations, the ongoing statements of opinions were largely related to the retouching of the damaged areas. In this case, in the way the conduct of the retouching operation was conceived, the good preservation of the paint layer in spite of the many items of damage was of crucial importance. The paint that had not yet flaked off the canvas retained its stratigraphic integrity with the well-preserved final lakes that are in many Titian paintings attenuated and damaged by frequent restoration operations. For the sake of the fullest possible presentation of the preserved features of the painter’s handwriting, a type of retouching was chosen that would imitate the surrounding paint in tone and facture in the damaged spots, and in larger zones would substitute for the missing form.

The retouching and other restoration procedures performed on the painting were not innovative in a technical sense, being rather part of tried and tested restoration practice, and with the exception of a few specific features, the greatest attention was devoted to precision of execution, made necessary by the character of the damage and indeed the importance of this work in the Croatian heritage.